Consider the global air pollution crisis alongside the desperate need to conserve resources and there’s only one possible conclusion: it’s time to extinguish the tradition of the garden bonfire.

As a boy, I was pretty whiffy. Out in the garden until dark, I would eventually come indoors, a noxious plume in my wake. A bath would purge most of the primal pong, but it lingered, deep in my pores, locked on my hair, regardless of scrubbing. It’s what happens when you dance until dusk around a smouldering bonfire, which you keep trying to turn into an inferno with a dash of paraffin (I stank of that, too).

Hiss, spit and the odd flare-up was all I usually got, along with stinging eyes – not the allegedly hot, sky-reaching and smokeless flames we see and read about, with tedious regularity, in gardening magazines. The reality of acrid neighbourhood smoke-outs, enforced coughing fits, November’s annual cremation of (living) wildlife, and ruined allotment afternoons don’t make it on to the pages. It’s high time they did.

Recently, during a spell when the air barely stirred, and a haze hovered over towns and cities, I caught that familiar whiff of childhood: bonfire smoke. Even mixed with wood smoke (from poorly understood and badly run wood burners), sulphurous coal fumes, and the wretched, head-spinning stench of burning plastic, the distinct, nostalgic aroma was there. It didn’t take much to jolt me from fleeting reminiscence; the catch on the back of my throat, and the reminder that, as one of my college lecturers pointed out about pesticides – ‘if you can smell it, it’s there’ – was ample. It’s there inside you, in your respiratory system, in your nose, throat and lungs.

Air pollution, from household and outdoor sources, is a growing and serious global threat. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates it is responsible for 6.5 million premature deaths worldwide each year – double the number of lives lost to HIV, tuberculosis and malaria combined, and four times the number killed annually on the world’s roads. According to WHO, 94 per cent of deaths attributable to outdoor air pollution are from non-communicable diseases: strokes, heart attacks, cardiovascular diseases and lung cancer. Respiratory infections are more likely if you breathe dirty, polluted air, which is also linked to mental illness, diabetes and kidney disease. Premature facial ageing, primarily of city dwellers, is likely to pull the biggest headlines, although the damaging effect of filthy air on children’s intelligence might just pip vanity to the post. Polluted air is largely caused by industrial activity, coal-fired power stations, inefficient, dirty transport (think diesel vehicles), and the burning of household fuel and waste. This last bit – burning waste – is where we gardeners can and must raise our game, by putting the box of matches away.

Renewable, earth-friendly gardening is about making something out of nothing; about reusing, recycling, repurposing; about nourishing new life from old; about reimagining ‘waste’ as valuable resource. I can’t think of one good reason why anyone with a garden or allotment needs to burn anything. Amid a global air pollution crisis, reading or hearing the vacuous ‘you get lovely ash rich in potash to spread around your fruit bushes’ just doesn’t cut it any more. Let’s cut it out.

Why my boyhood self ever thought I could build an inferno out of piles of wet couch grass and other weeds, or grass clippings and soggy leaves, I’ll never know. Soft, sappy garden and hedge trimmings can all be easily composted into soil food. If you’re struggling with volume, you can always, as a last resort, divert some to your garden waste bin/bag (which can also be used for pernicious weeds and diseased plant material). Local authorities collect these garden resources and send them to large-scale composting sites, where they’re transformed, at high temperatures, into peat-free soil improver which you can import back onto your plot. Please, please, please don’t ever think about burning autumn leaves; they can be turned, with the help of time, into soil-boosting leafmould.

If you’re tempted to send away your woodier resources, such as hedge trimmings, and the prunings from both edible and ornamental trees and shrubs, for off-site composting, don’t! – and whatever you do, don’t burn them. There are myriad fates for woody material benefitting wildlife, the soil, and your plot in general, without mucking up our air.

First, there are the bigger, log-sized bits. These can simply be stacked in a pile – as big as you like – in an out-of-the-way part of the garden. Don’t stack them too tightly; leave plenty of gaps for wildlife (toads, frogs, hedgehogs) to move in. As the logs touching the soil decay, they become a miniature, self-contained ecosystem. As the pile sinks, add more logs. If you reach log overload, offer them to neighbours with a wood burner, or put them outside your gate with a ‘free firewood’ sign pinned to them (pray that the recipients know how to season it properly first). Failing that, send them off for composting.

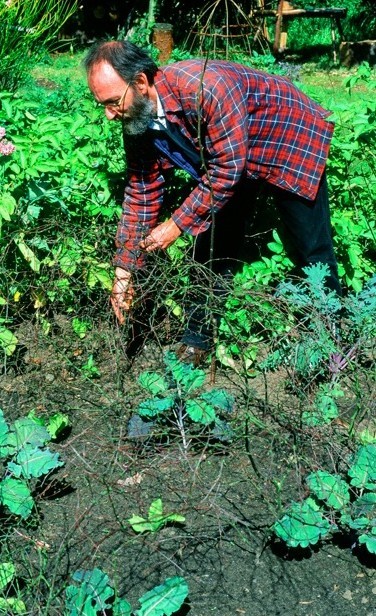

When you get to the thinner stuff (4cm or less in diameter) your options widen. Most woody prunings make excellent (and free) plant supports. In my garden, hazel shoots 1.8m long, pushed into the ground then tied together at the top, never look better than when smothered with sweet peas. Thicker stems, trimmed of their twiggy sideshoots, are perfect for climbing crops such as runner beans. Really whiskery bits from the ends of shoots can be pushed in among pigeon-prone crops such as brassicas; they hate to land where there’s any kind of obstruction, and will fly off again in terror. Trust me, it works.

Any thinner woody prunings that you can’t redeploy in your borders or kitchen garden, you can use in other ways by shrinking them down in size using a shredder; most will take branches up to 4cm across. Electric ‘roll and crush’ types are far quieter than noisy ‘impact’ models (which soon bug the neighbours). You can use the shreddings as a weed-stopping mulch, or as all-weather paths on an allotment. But a much better use for these soft, sappy, nutrient-rich bits is to spread them over any soil you want to improve and work them into the surface. I’m using ‘chipped branch wood’ to revitalise the soil in parts of my own garden; it’s a lot easier than digging, and if you run your shredder on ‘green’ electricity, there’s no fouling of our air by a distant power station.

The other best thing to do with shreddings is use them as part of your compost mix, where they’ll gradually rot down, the greener, thinner bits going first – or you can just pile them up in a heap of their own, where they’ll heat up and then cool down, before fungi move in and start to break them down. After a year or more, the dark brown woody fragments can be used in a home-made peat-free potting mix. If all else fails, you can offer bagged-up shreddings to your neighbours to mulch their own gardens (or should they be about to set light to some, offer to take their woody prunings away). If neighbourliness blossoms, you might even invest in a shredder to share.

The air I breathe now, as a grown-up gardener, is sometimes whiffier than I am (not counting my wellies). I banished bonfires here many moons ago, and I’ve never looked back. Our gardens and allotments are rich with solutions to numerous problems pressing in around us. An easy win is for us to stop sending their resources up in smoke.

Text and images © John Walker

Find John on Twitter @earthFgardener