In and out, back and forth, to and fro: this is the season of ever-watchful gardeners and peripatetic plants.

Blessed as I am to be able to work from home, these days more and more of my time is devoted to commuting – although I’m not to-ing and fro-ing for work, but for the love of plants.

This commute, involving only footsteps back and forth between my greenhouse and garden, is becoming an increasingly crucial one. In a wildly unpredictable, rapidly changing world – parts of the UK have just had the driest March since before my birth – nothing about gardening is fixed or solid any more. Predictability, certainty and reliableness are usurped by flux, fitfulness and volatility.

Gardening has always been about rubbing along with our weather’s capricious nature, but we’re now sowing, potting, planting and growing in whole new territory. Climate breakdown means that in order to garden well, successfully and productively, we are going to have to skill up, hone our horticultural wits and grow ever more guile.

March here in North Wales felt like an unfamiliar land; it rained little, and for long, magical periods, the sun came up gold, shone all day amid cloudless blue, then sank in fire on the horizon. The soil dried out, bumblebees dared seek out the first dandelions, and you could leave stuff – jumpers, secateurs – out overnight, certain it wouldn’t rain on them. It usually does in colossal amounts here in land once swathed in Celtic rainforest.

Much of my spring commuting in the last decade or so has involved bringing pot-grown plants back into my greenhouse to give them a break from the rain. This isn’t always the heavy, damaging rain that flattens seedlings and young plants, but light, persistent, compost-waterlogging, root-rotting rain that falls non-stop for a week.

In the old weather days, a downpour now and then would see to the watering, while the fine spells in between ensured that the compost never stayed sodden for days on end. In this new, mercurial weather world, I can’t risk leaving smaller, just-potted plants at the mercy of the rain’s persistence – or its sheer force. A warming world means there is more moisture in our atmosphere, which shows its most extreme hand as the catastrophic flooding we’re now seeing globally.

Gardening might seem insignificant in the grand scheme of extreme weather events, but if you’re gardening with intent for food, this stuff matters. A glance at the increasing unpredictability of crop harvests worldwide, and the knock-on effects on food prices, should urge us all to grow more stuff to eat (and to share those food-growing skills widely). Perplexingly for many, food doesn’t grow on climate-impact-prone supermarket shelves.

While there’s no great hurry to bring in rain-soaked plants, hail has me whipping my skates on. There’s not a second to lose when a hailstorm strikes; one stone can terminate a seedling or young plant, or do it irreparable damage. We’re experiencing storms here in the UK that can drop hailstones big enough to shatter greenhouse glass – and they will only get bigger.

If I’m not around, it’s too risky to leave plants out on close and stormy, shower-prone days, so they’re either stood under repurposed secondary glazing units, or stay in the greenhouse. If your greenhouse is at bursting point, standing plants under the eaves of a building helps shelter them from spring and summer storms, be it torrential rain, hail or both.

What falls from the sky isn’t the only spring hazard in our keeping-us-on-the-hop world – what shines from it can also cause damage. Sudden spells of hot sunshine are intensified in a greenhouse, polytunnel or other structure harvesting sunlight. Following a long spell of cool, sunless weather, seedlings and young plants get a bit soft. If they’re suddenly bathed in unseasonably full-on sun – especially when magnified by glass – they can burn, their scorched leaves setting growth back.

The first rule of avoiding scorch is to work out where the hot spots are in your greenhouse, and avoid putting plants there; the metal staging in one corner of my lean-to gets so hot I swear it could boil water. It’s a no-grow zone on hot spring and summer days. During a spell of ‘extreme sunshine’, I shuttle seedlings away from the glass, and lay a white cotton sheet or some just-leafing hazel branches (any leafy shoots will do) over the greenhouse roof. Plastic-free, they work a treat.

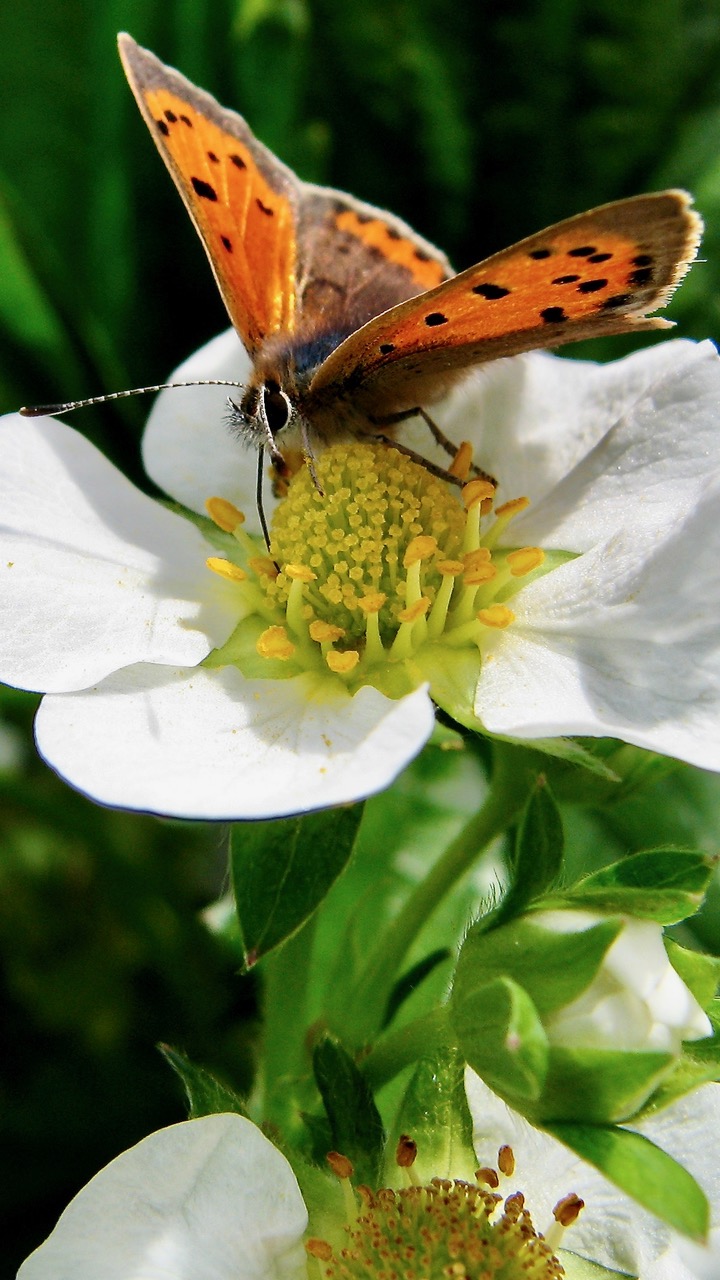

Stormy spells often end with flashes and bangs and sudden downpours of torrential rain or hail, or both. My potted strawberries are now on storm watch; if the skies darken, the plant commute begins as I swiftly bring them back into the greenhouse (keep your carrying trays handy). The savagery of grey squirrels means that if I am to stand any chance of tucking in to a strawberry, my plants must be pot-grown and coddled in my greenhouse (they’re doomed outdoors). I get earlier fruits doing it this way, and the constant to and fro from greenhouse to garden and back again is worth every fruit-yielding footstep.

My shuttling strawberries are protected from not just squirrels, berry-stabbing blackbirds, mice, voles, snails and slugs, but also from wind, rain, hail, snow and frost. They get the best of both worlds: the shelter of the greenhouse, especially on starry nights, and all the advantages of being outdoors on fine, life-filled spring days.

The biggest boon from me taking them in and out is that outside, their flowers get visited and pollinated by ravenous insects, meaning a reliable set of fruits; if they stayed indoors, some pollinators would find them, but I want fertilisation max. Overwintered hoverflies, bumble and solitary bees, and other early nectar- and pollen-seekers find ample in strawberry flowers, so I plonk them next to dandelions and other early flowers already fizzing with insect life.

Visiting hoverflies endow my strawberries with something else: pale, pill-shaped eggs that hatch into snot-like grubs, each capable of eating 50 aphids a day. Potted strawberries, mollycoddled in my greenhouse, are catnip to aphids, which quickly set up camp on their soft, pampered leaves. When the plants move outside, the hoverflies detect them and lay their eggs nearby. Later, as the aphid-free berries redden under cover (commuting ceases once the fruits set), hoverfly grubs mature, pupate, then hatch into adults that fly off in search of aphids on the by-then-planted tomatoes.

All the to-ing and fro-ing, with plants constantly on the go, feels worth it when it rewards me with such beneficial extras, and sharpens my gardening guile.

It’s darkening outside and thunder’s rumbling. Time to get those strawberries moving…

Text and images © John Walker

Join John on X @earthFgardener